Sitting on a cold, rainy January day with an older man in his early 80’s in the historic Washington Hall of the Central District in Seattle, I was in foreign territory. Here I was sitting where the patrons had been in the company of Mahalia Jackson, Billy Holiday, Quincy Jones, Jimi Hendrix and many other renowned black musicians, not to mention speaker Martin Luther King, Jr. What I didn’t know about the history of jazz in Seattle! The city was a jazz combo town because, although the big jazz bands were at their height, downtown Seattle venues were closed to black musicians. The big jazz bands were predominantly African-American. The small black population of Seattle alone could not support 15-20 black musicians on a payroll, so they supported smaller “combo” bands.

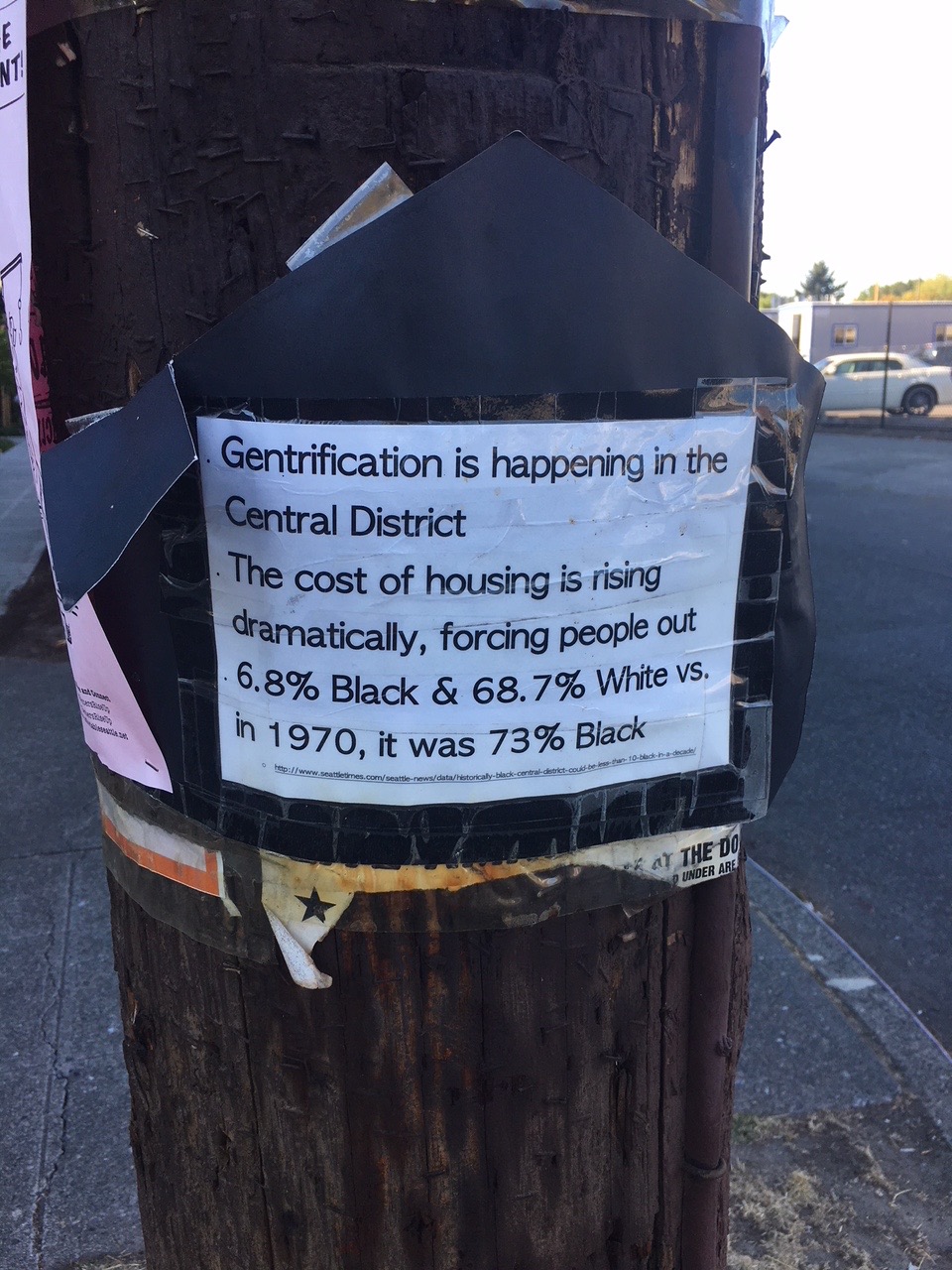

By 1970 the Central District was 73% black, but today it is 6.8% black and 68.7% white. The barbers in the only black barbershop in the neighborhood now feel strangers in their own neighborhood. When taking off their barber aprons and stepping out into the street toward their homes, the barbers are accosted by members of the white population, asking, “what are you doing here?” Their incredulous answer rings small in the newcomer’s ears, “this is my home.”

I turn to the older man while he explained that the Dred Scott decision stayed on the books, regardless how bad the decision was at the time. “Basically,” he said, “we black people have been designated animals. We were never considered human. It’s okay to shoot a black man today, but it is a crime to shoot a dog.” The white man on the other side of me said, “wow, I have never considered, nor had to consider, that I might not be human!”

The older man continued, “So why do we need a civil rights act? Is it because we have still never been declared human beings?” I wince inside. I remember being told, when we tried to support affordable housing in our rural community 28 years ago, “go to Seattle where the real “n’s” live!”

Behind all these hate-filled sentiments lies so much fear, so much insecurity, and so much conscious and subliminal messaging. I am aware that these sentiments are hiding within my island as well, because the entire history of this region speaks of xenophobia. So even here, in the place I call home, I take the words of Toni Morrison to heart, “This is precisely the time when artists go to work—not when everything is fine, but in times of dread. That’s our job!” She tells us we must speak up. We must bring it all out into the open, “into the Light,” as some of us would say. So, despite the fact that two of our Black Lives Matter signs have been stolen, I today will put up yet another.

(P.S. The sign lasted one night.)

Further Resources: Waking Up White by Debby Irving, Between the Worlds and Me by Ta-Nehishi Coates. Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson, and The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander.